University News & Insights

19/11/2025 2025-11-26 18:45University News & Insights

University News & Insights

Teaching and Learning Seminar Series

Focus on Active Learning to enhance academic lectures and engage students Seminar summary using NotebookLM (AI generated)

Leading With Purpose: How Strategy Shapes Transformation in Higher Education

Transformation requires design,

Euro University of Bahrain signs a Memorandum of Understanding with the Judicial and Legal Studies Institute under the Ministry of Justice in the Kingdom of Bahrain

Euro University of

Teaching and Learning Bulletin

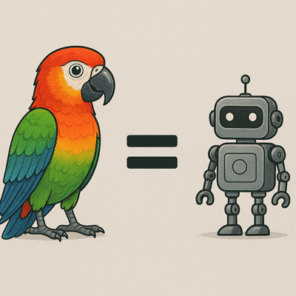

Supporting Responsible AI Use (This week the TLC has been exploring how we engage our students in using AI wisely and well.) As AI tools become part of everyday academic practice, from ChatGPT and Grammarly to NotebookLM and beyond, our students increasingly turn to them for speed, structure and inspiration. We cannot control this. Instead, our shared task is to encourage responsible, reflective and academically grounded use of these tools. In this week’s bulletin, I want to showcase what we discussed with our students in their recent TLC seminar to explore how we can guide students towards owning their work, engaging with ideas, and developing the judgement that characterises genuine higher learning. The role of AI and how it can be used well AI offers fluency, speed and access to a vast archive of prior human output, but it does not think, generate genuinely new insights, or evaluate competing claims. The idea of the ‘stochastic parrot’ needs to ground our thinking when discussing AI’s use in academic assignments. For our students and for their engagement with the content and framework of their work, we need to focus on the notion that AI reproduces patterns rather than producing original reasoning. For students, this means AI should be seen, if at all, as a starting point; a point from which to critique, adapt and contextualise information that is given, rather than something to accept uncritically. In the session with the students, we saw how AI can sound authoritative even when offering contradictory or superficial responses. The marketing task we reviewed allowed AI to mirror our response and was equally able to frame a campaign as “excellent” or “poor” simply on the direction of the prompt rather than any underlying conceptual reasoning. For our students, this means AI might work as a generator of plans and ideas that then require their own interpretation, analysis, justification and contextualisation. AI can accelerate routine processes, but unreflective dependence risks undermining the very learning we all value. When students begin by accepting AI’s suggestions uncritically, they risk producing work that is generic, disconnected from course material, and ultimately misaligned with the aims of their programme. When students depend on AI they ‘outsource’ too much of the thinking process, they lose opportunities to understand the theory and develop their analytical voice. Moreover, as the session discussion emphasised, students who lean heavily on AI risk losing ownership of their responses: they present polished sentences without really engaging with the ideas or participating in the process of developing themselves for the future world of work. Helping students to reflect on the limits and appropriate uses of AI is therefore not simply a matter of academic integrity. It is central to building professional judgement, confidence and ethical awareness that will matter far beyond coursework. Academic programmes aim to develop graduates who interrogate evidence, take positions, justify decisions and adapt ideas to organisational realities. These reflective capacities require students to engage meaningfully with theory and develop intellectual ownership of their work. How we encourage responsible use We can encourage responsible use by a). promoting visible learning processes, such as drafts, notes and reading logs; b). showing that coursework is designed to be achievable, through unpacking and providing clear assignment briefs and module materials; c). focusing on ensuring students pose questions that critique AI outputs; d). emphasising student ownership of their work; and e). creating space for open discussion about AI use. A). Promote ‘AI-visible’ learning processes B). Show that good coursework is fully achievable without AI C). Make reflective questioning routine D). Emphasise the principle of “owning the work” E). Create space for students to talk openly about their AI habits TLC support The Teaching and Learning Centre can help by supporting assessment design, providing sample activities that build AI literacy, helping develop reflective portfolios, and offering workshops on critical digital skills and reflective practice. Our responsibility is to guide students towards using AI wisely. By modelling reflective questioning and designing tasks that reward genuine thinking, we build a learning culture rooted in transparency, engagement and academic integrity.

Success Belongs to the Community, Not the Individual

Real success rarely comes from a single leader, a single decision or a single moment. It comes from a connected, empowered and well-motivated community — one where people support each other, challenge each other, and feel part of something bigger than their own role. And it’s never instant. There isn’t one announcement, one hire or one initiative that suddenly fixes everything. Sustainable progress is built through small improvements made day by day, week by week, month by month. A conversation that brings clarity. A process made slightly smoother. A department that collaborates a little more closely than it did the month before. On their own, these moments seem modest. But over time they add up. You can sense it when the momentum begins to build. There’s an energy that moves through an organisation when people feel connected and empowered. Ideas surface more easily. Problems are tackled earlier. Teams become quicker, clearer and more confident because everyone, in every corner, is contributing — often in ways that are quiet but deeply meaningful. To create an environment for community success we’ve designed and published a culture with purpose. When things are going well at EUB, you can feel the buzz before you can fully describe it. It shows up in how readily people help each other, in the ease with which colleagues share ideas, and in the pride people take in the work they do. It’s the product of hundreds of small decisions and steady improvements made across the university, not a single turning point. Leadership has a role, of course. But leadership is less about providing all the answers and more about creating the conditions for this gradual, collective acceleration: clarity of direction, safety to speak honestly, room to innovate, and recognition for progress — even when it’s incremental. The strongest organisations are those where ownership is shared. Where victories feel collective, and challenges bring people together rather than push them apart. When motivation runs through the whole community, small improvements accumulate naturally, and momentum becomes self-reinforcing. As we look ahead, my hope is that we continue to build a university where success is not a moment or a spotlight, but a shared journey. A place where confidence grows, contribution is recognised, and the power of small, steady improvement is felt in every department. Because in the end, great outcomes don’t belong to one person. They belong to the community. “Every successful individual knows that his or her achievement depends on a community of persons working together.” — Paul Ryan

Teaching and Learning Seminar Series

Focus on Scaffolding to support student learning in an international setting Seminar summary using NotebookLM (AI generated)

EUB Announces Major Achievement: University of London Degrees Delivered at EUB Now Officially Recognised on Bahrain’s National Qualification Framework

Euro University of Bahrain (EUB) announced that the Bahrain Education & Training Quality Authority (BQA) has published the alignment results listing six University of London (UoL) degrees delivered by Euro University of Bahrain (EUB) on the Bahraini Register of Recognised Qualifications at NQF Level 8. The publication follows the completion of the Alignment of Foreign Programmes to the National Qualification Framwork (NQF) project. The programmes included aligned with the Bahraini NQF include: Bachelor of Science in Business Administration (general) and three pathways, Bachelor of Science in Computer Science, and Bachelor of Laws (LLB). These programmes are structured and designed to meet the UK Frameworks for Higher Education Qualifications (FHEQ) at Level 6 (undergraduate honours level), corresponding to NQF Level 8. The alignment project was an opportunity to visit qualification design against level expectations, assessment standards and academic integrity, Institutional quality assurance and governance, Student support, learning resources, and information, and Credit structures and completion routes. Achieving the alignment ensure suitability of provisions which will enable learners’ mobility. “This milestone recognises the rigour of our academic provision and delivery, as well as the strength of our student support in meeting the Bahraini standard for degree-level education,” said Prof Andrew Nix, President of EUB. “It strengthens confidence among students, employers, and partners that EUB’s internationally awarded programmes meet Bahrain’s national quality standards.” “The outcome reflects our collective commitment and evidence-based practice across every department,” said Dr. Reem Al-Buainain, the Vice President of EUB. EUB extends its appreciation to the BQA for its professional collaboration throughout the “Alignment of Foreign Programme”—marked by clear guidance, timely communications, and rigorous review—and to the HEC for its continued stewardship of Bahrain’s higher-education quality ecosystem, ensuring policy coherence, transparency, and confidence in nationally recognised qualifications.

Teaching and Learning Bulletin

Observation as a way to ‘notice’ and enhance reflective practices As we reach the close of our recent round of teaching observations, feedback and discussions, I want to use this bulletin to reflect on what we have being doing together and the impact this has on our learning culture and our teaching and learning practices. The intention behind the way in which the observation cycle has been designed, and the follow-up processes that accompany it, is to ensure that observations are not viewed as mere checkpoints of quality. Instead, they should be seen as opportunities for professional dialogue, for insight, and for growth. Observations are also useful activities to encourage and engage in developing ‘teacher noticing’, something I will return to in a later bulletin and will become a focus of one of the TLC seminars. The observation process helps us look closely at our practice: how we prepare, how we teach, how we engage, and how we respond to our students in real time. It also offers space for reflection, that is, moments to ask guiding questions, raise awareness of elements in our teaching that could improve, and share in collective professional development. Our observations aim to explore elements that shape the learning experience: lesson preparation and structure, achievement and clarity of learning outcomes, relevance of material, activity design, responsiveness to student needs, and the professionalism with which we conduct ourselves in class. This focus aligns with Advance HE’s Professional Standards Framework (PSF), which places self-awareness, professional identity, and evidence-based improvement at the centre of teaching excellence. Through observation, each of us can evidence and show our direct engagement with the PSF’s three dimensions (activity, knowledge, and values) demonstrating our ability not only to teach, but to reflect on what we do and why it matters. When approached professionally, observation shifts to an activity of shared scholarship. Schön’s (1983) notion of reflection on action provides a useful tool which encourages us to view observations as catalysts for revisiting lessons, analysing decisions, and considering alternative strategies for future sessions. Our observation framework aims to support this process. When we, as academic lecturers, take time to discuss teaching materials, interaction quality, or the use of formative assessment, we engage in reflective practice (this links to the previous bulletin). This reflection, which can be further enhanced through the observation cycle, leads to ‘noticing’, asking questions, and finding shared answers: • What worked well and why? • How did my students respond? • How might I adapt next time? As Colomer et al. (2020) note, reflective learning transforms experience into insight, enabling educators to develop responsive and sustainable teaching practices. A means of enabling the reflection is through observation when done in the right way. Atkinson and Bolt (2010) note that teaching observations are most effective when they become collaborative spaces for feedback and reflection, rather than evaluations imposed upon us. For staff, observation should offer affirmation and insight. It seeks to enhance the confidenc of the lecturer while providing a structured opportunity to question and refine practice. Feedback from the Teaching and Learning team helps us see not just what happened in the classroom, but how our teaching aligns with our intentions and desired learning outcomes. This process aims to strengthen professional identity, enabling each of us to view teaching as an evolving practice. For the organisation regular observations build collective confidence in the quality of learning and teaching. They also foster a community of shared standards and support, echoing Advance HE’s vision of ‘a sector that learns from itself’. At EUB, this means being a university that reflects, learns, and grows through its practices and its own reflective process. For our students, the benefits are clear. When staff engage in reflective observation cycles, the result is teaching that is more responsive, inclusive, and evidence-informed. Students see that their lecturers are invested in continual improvement as well as being open to feedback and committed to providing the best possible learning experience. Transparency is key to cultivating professional confidence. When observation feedback is shared collegially and viewed through the lens of improvement rather than judgement, it builds trust. Our most recent observation cycle shows that staff value opportunities to discuss how lesson sequencing, activity design, and feedback mechanisms aim to support student learning. This spirit reflects Atkinson and Bolt’s (2010) emphasis on peer dialogue and professional learning communities and resonates with Advance HE’s commitment to embedding continuing professional development (CPD) within institutional practice. When we open our academic sessions to one another this normalises professional curiosity. To foster this further the TLC will be looking to promote a future phase of observations which will aim to integrate peer observations into our T&L cycle. The Teaching and Learning Centre (TLC) continues to support observation as a developmental process, not an isolated event. We can work with you to: Our collective aim is to nurture a reflective culture that celebrates what we do well, while encouraging continuous improvement. Observation, reflection, and professional dialogue should help build the confidence and transparency that underpins our work at EUB and develops a professional, learning-oriented academic community. Thank you to all of you for participating in the observation cycle and enhancing EUB’s culture of teaching and learning. References Atkinson, D. and Bolt, S. (2010) Using teaching observations to reflect upon and improve teaching practice in higher education. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(3), pp.1–19. Colomer, J., Serra, T., Cañabate, D. and Serra, J. (2020) Reflective Learning in Higher Education: Active Methodologies for Transformative Practices. Sustainability, 12(9), p.3827. Harrison, J. (2012) ‘Professional Learning and the Reflective Practitioner’, in Dymoke, S. (ed.) Reflective Practice and Professional Development in Education. London: Sage Publications. Schön, D.A. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books.