Teaching and Learning Bulletin

Learning Outcomes: Linking Constructive Alignment and Employability Skills I recently led a Teaching and Learning seminar that focused on how we write, use, and reflect on learning outcomes. The session explored constructive alignment (Biggs and Tang 2011) and how our learning outcomes can do more than list intentions. Learning outcomes should become active tools for designing meaningful learning experiences. In addition to this we looked at ways we can complement good learning outcomes in ways that help our students develop employability skills alongside academic knowledge. What are learning outcomes? Learning outcomes articulate what students should be able to do, demonstrate, or understand by the end of a session, module, or programme. Biggs and Tang (2011) describe constructive alignment as the process of ensuring that learning outcomes, learning activities, and assessments work together in an integrated way to support deep, active learning.In the seminar we focused on the framework, thinking about the following questions: When these three questions align, the outcome verbs (“explain”, “analyse”, “apply”) drive the learning design. Activities should engage the same verbs, and assessments should allow students to demonstrate them. As the presentation and ppt slides aimed to emphasize “learning is about what the student does, not what we as teachers do”. Why does this matter? The concept of constructive alignment is influential in higher education because it connects curriculum design directly to student learning. However, as Loughlin, Lygo-Baker, and Lindberg-Sand (2021) note, alignment should not be treated as a bureaucratic exercise but reclaimed as a professional tool that helps lecturers think deeply about the purpose and coherence of their teaching. When learning outcomes are genuinely student-centred, they become more than statements for quality assurance validation. Learning outcomes help clarify the intent of a module, guide student engagement, and make assessment transparent. Most importantly, I believe they allow us to build in transferable and employability skills that prepare students for life beyond the classroom. How can we seek to integrate Learning Outcomes and employability skills in practice? The simple answer here is to make explicit what it implicit in the actions and activities our students participate in. As lecturers we can raise awareness in our students of the type of activity or task they are doing and how this links to employability skills. It gives purpose to the task. Our discussions during the session showed that constructive alignment is most effective when it is lived in the design of classroom activities. For example, in the Law Unit 1 session, lecturers explored how the verbs used in outcomes (“explain”, “discuss”, “analyse”) could guide activity design that develops specific employability skills. Some examples included: Each of these activities supports both the intended learning outcome and a transferable skill such as collaboration, problem-solving, or communication. In turn this aligns academic learning with employability development. Embedding employability skills through outcomes Employability at EUB is not an add-on but integral to our graduate journey. By writing outcomes that reflect both disciplinary knowledge and transferable skills, we can show students how classroom learning connects to the competencies valued by employers and society. For instance: Through constructive alignment, the learning outcomes we select and the activities we design to support them can explicitly nurture the attributes and employability skills we value across the university. How the Teaching and Learning Centre can support you As the seminar aimed to demonstrate The Teaching and Learning Centre works with academic staff to refine and align learning outcomes, teaching activities, and assessment design. We provide guidance on writing outcomes that integrate both academic and employability dimensions, as well as workshops and peer-sharing sessions that showcase effective practice. Constructive alignment is not a checklist. It is a way of thinking about teaching that aligns learning and skills development. By consciously aligning our outcomes, activities, and assessments, we not only make our teaching more coherent but also empower students to become active, employable learners ready to shape their own futures. In future seminars, we will continue to explore ways of connecting constructive alignment with employability frameworks, ensuring that our students can clearly see the skills they develop through their studies. References: Biggs, J, and Tang C. (2011) Teaching for Quality Learning at University: What the Student Does. 4. ed. SRHE and Open University Press Imprint. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill, Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press. Loughlin, C, Lygo-Baker, S & Lindberg-Sand Å (2021) Reclaiming constructive alignment, European Journal of Higher Education, 11:2, 119-136, DOI: 10.1080/21568235.2020.1816197

What Do We Value in a University?

This week I’ve been attending education fairs and meeting prospective students and their families. It reminded me that to maximise

Teaching and Learning Bulletin

Graduate Attributes: Exploring how our students shape their futures through skills, values, and reflection In this post, I wanted to share and reflect on a recent session with our new students focused on our Graduate Attributes. The students worked in small groups to discuss and consider the skills, values, and characteristics that underpin our five EUB Graduate Attributes. With plenty of post-it notes and a lively discussion, the session aimed to give students the opportunity to think about what our graduate attributes can mean to them personally, and how they can take ownership of them during their time at university What are EUB Graduate Attributes? Graduate attributes represent the essential skills, knowledge, and qualities that universities seek to cultivate so students can thrive both during and beyond their studies. At EUB we talk about five graduate attributes that we believe shape not only academic success, but also the kind of people and professionals our students become: Together, these attributes provide a framework for the kind of graduates we aspire to nurture: adaptable, innovative, and socially conscious leaders. Why do graduate attributes matter? Graduate attributes are more than abstract ideals. Research and sector trends consistently highlight that employers and communities value not only subject expertise, but also critical thinking, digital literacy, cultural awareness, and social responsibility. For our students, these attributes open pathways to professional success and empower them to make meaningful contributions to society. By working actively with the attributes during their studies students begin to see how their academic and extracurricular experiences interconnect, shaping both who they are now and who they are becoming. How can we bring attributes to life in practice? Our recent session provided a clear example. In small groups, students explored each attribute, noting the skills, behaviours, and values they believed were most relevant. Post-it notes clustered around each attribute raised awareness and attention as well as capturing a range of insights: • Problem-solving means not just finding answers, but asking better questions. • Social responsibility is about small everyday choices as well as big community projects. • Being globally aware includes listening to peers from other cultures right here at EUB. This collaborative, interactive format encouraged students to define attributes in their own words and recognise them in their everyday academic and personal lives. As lecturers, we can build on this approach by embedding graduate attributes into our curriculum, our seminar sessions, assessment activities, and feedback conversations — helping students continually connect their active engagement in different sessions with the wider global community they participate in. Graduate Attributes and the Falcon Award At EUB, we are taking the opportunity to encourage students to explicitly engage with our Graduate Attributes. The Graduate Attributes have been embedded into our Falcon Graduate Attribute Award. This award will recognise students who demonstrate high engagement with the attributes through self-awareness and reflection. Working towards the award involves: Students who complete the process receive a certificate and LinkedIn badge, formal recognition that enhances their employability and professional profile. More importantly, they gain confidence in articulating the value of their EUB education, both to themselves and to future employers. The role of the Teaching and Learning Centre The Teaching and Learning Centre collaborates with staff across EUB to embed graduate attributes meaningfully into teaching, learning, and assessment. We provide training, guidance, and opportunities to innovate in curriculum design, helping colleagues align their modules with the attribute framework. During the academic year, we will also run seminar sessions where staff can share practice, and students can showcase how they are developing the attributes through their studies and extracurricular activities. Together, these conversations ensure that graduate attributes remain a living, dynamic part of our ethos, not just a list of words. Graduate Attributes embedded in EUB teaching practice The session with the students reminded me that when students are invited to actively engage with our graduate attributes, they bring fresh perspectives and a strong sense of ownership. As staff, we have the opportunity to harness that energy, embedding attributes across all aspects of the student journey. I hope this reflection sparks conversations in your teaching teams. If you would like to explore further how graduate attributes can be integrated into your modules or how your students can participate in the Falcon Graduate Attribute Award please connect with us at the Teaching and Learning Centre. Together, we can ensure that our graduates leave EUB with not only academic excellence but also the confidence, skills, and values to shape a better future.

Teaching and Learning Bulletin

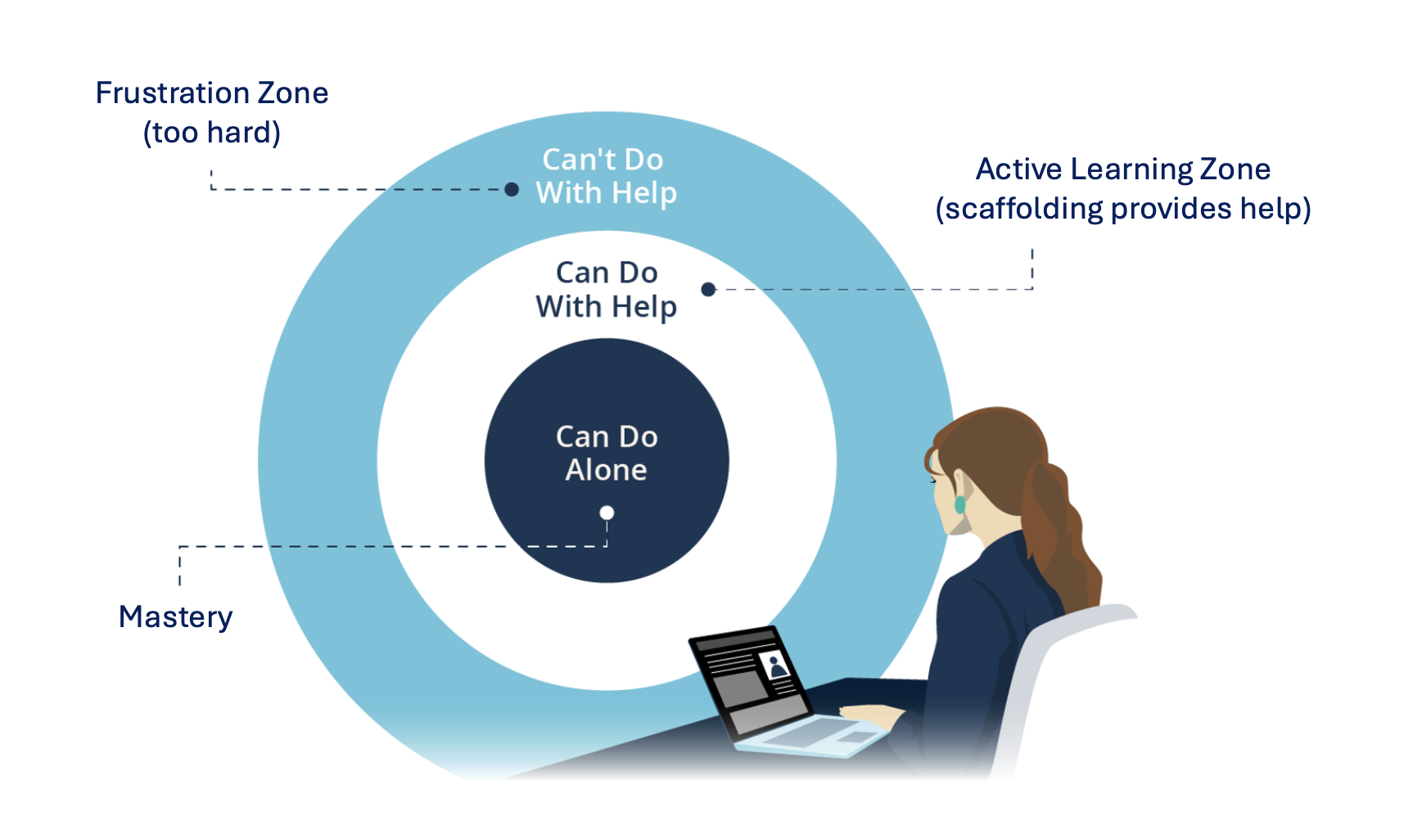

Placing our students at the heart of the learning process. Active Learning: what it is, why it matters Welcome to this edition of our Teaching and Learning Bulletin (now shared as a blog).Our aim is to offer ideas and approaches that can enrich our students’ learning experiences and encourage us to look at our teaching and learning practices from fresh perspectives. Building on discussions from our recent Teaching and Learning session during staff induction week, I’d like to continue embedding into our Teaching and Learning ethos the concept of active learning. This is an approach that places our students at the heart of the learning process. As a reminder of what we explored together, you’ll find below an overview of what active learning is, why it matters, and how we can begin to embed it meaningfully in our classrooms. What is active learning? Active learning places students at the centre of the educational process. Instead of sitting back as information is passively provided to them, students are encouraged to interact with content through tasks that require reflection, application, and collaboration. This approach is grounded in constructivist learning theory, which recognises that learners build new knowledge by connecting it to what they already know (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 1999). Social constructivism, as articulated by Vygotsky (1978), adds that learning is shaped through interaction — reinforcing the value of collaborative and cooperative environments in our classrooms. In practice, active learning can take on many forms from pair work and structured discussions, group problem-solving, debates, to case studies and case-based tasks. What matters is that students are thinking with the material, not just about it. Why does active learning matter? There is a growing body of evidence showing the impact of active learning. Freeman et al. (2014) found that it significantly improves student performance and reduces failure rates compared to traditional lectures. Similarly, Prince (2004) and Michael (2006) argue that active learning not only promotes deeper understanding but also develops the transferable skills our graduates will need. Importantly, the purpose of active learning goes beyond content mastery. It fosters critical thinking, problem-solving, and metacognitive awareness (Anderson et al., 2005; Kember & Leung, 2005). It also creates a more inclusive, motivating environment that benefits students from diverse backgrounds (Eddy & Hogan, 2014; Theobald et al., 2020). When students feel engaged and supported, they are more likely to take ownership of their learning. How can we make active learning work? While the benefits are clear, successful active learning requires intentional planning and facilitation. As lecturers, this means designing learning environments that encourage participation, risk-taking, and reflection. Activities should be aligned to learning outcomes and structured in ways that scaffold students’ engagement, giving them the confidence to participate fully. It can be tempting to see active learning as a single strategy or activity. In reality, it is a mindset that places our students as active participants in constructing their own learning journeys. This said, on the TLC Moodle page you will find practical examples of active learning. These examples range from project-based assignments where students participate in real-life assignments, to in-class activities that encourage students to remain engaged and active during lectures and seminars. These types of activities include using online survey tools, like Kahoots, to present concept checking questions during the lecture or prompt discussion at the beginning of a session to raise awareness of misconceptions, shared understanding and individual knowledge. The examples also include think-pair-share questions that students can participate with during and towards the end of academic sessions. How the Teaching and Learning Centre can support you The Teaching and Learning Centre collaborates with you to provide training, support and guidance to help you plan, innovate and develop your use of active learning activities and techniques. Our aim is to work alongside you as you explore and embed new approaches in your teaching. Throughout the academic year, we will run seminar sessions that bring colleagues together to share and learn from one another’s practice. These sessions will highlight different ways in which active learning can enhance our students’ experiences — from fostering deeper understanding to building their confidence and independence as learners. By connecting theory with lived practice, and by learning from each other, we can build a vibrant, collaborative culture of active learning across our classrooms. Moving Forward As always, we hope this piece prompts fresh conversations in your teams and inspires you to try something new. If you would like to explore active learning further or discuss how it might work in your own teaching context, please do get in touch with us at the Teaching and Learning Centre, come along to our regular seminars or put your name forward to run a seminar in collaboration with us. Let’s continue to learn from and with each other as we shape rich, engaging learning environments for our students. Some Useful References: Anderson, W.A., Mitchell, S.M. and Osgood, M.P., 2005. Comparison of student performance in cooperative learning and traditional lecture-based biochemistry classes. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 33(6), pp.387–393. Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L. and Cocking, R.R., 1999. How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Brame, C.J., 2016. Active learning. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Available at: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/active-learning/ Eddy, S.L. and Hogan, K.A., 2014. Getting under the hood: How and for whom does increasing course structure work? CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(3), pp.453–468. Freeman, S., Eddy, S.L., McDonough, M., Smith, M.K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H. and Wenderoth, M.P., 2014. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), pp.8410–8415. Kember, D. and Leung, D.Y.P., 2005. The influence of active learning experiences on the development of graduate capabilities. Studies in Higher Education, 30(2), pp.155–170. Kozanitis, A. & Nenciovici, L., 2023. Effect of active learning versus traditional lecturing on the learning achievement of college students in humanities and social sciences: A meta-analysis. Higher Education, 86, pp.547–569. Michael, J., 2006. Where’s the evidence that active learning works? Advances in Physiology Education, 30(4),

The Lessons That Come From Getting It Wrong

In education, as in leadership, we tend to celebrate what goes right. The project that succeeds. The idea that works.

Growth Mindset: Evidence and Application

Carol Dweck’s research at Stanford University has reshaped how we think about learning. Her central conclusion is simple but powerful:

Writing Papers that Get Published: Solving Problems that Matter

I recently came across a lecture by Larry McEnerney from the University of Chicago’s writing programme. It’s remarkable since it

Why Struggle Matters: Active Learning, AI and the Future of Student Success

Simon Cleary, our Academic Director, recently reminded faculty that the classroom is not the place for passive listening. The real